We’ve been writing about a disclosure law in Europe for datacentres called the Energy Efficiency Directive quite a lot on this website, because if you want a fossil-free internet, then understanding if you’re on track is important. Recently our friends at Leitmotiv Digital shared some research about datacentre disclosures in the Netherlands, based on data shared by the Dutch government, and it spurred us to look into what’s happening in the largest datacentre market in Europe, Germany. Or rather, what’s not happening. There’s a colossal gap in German datacentre reporting, that suggests the biggest players are not playing ball – we explain the implications of this, and where to learn more.

A recap: what is EED this disclosure law, and why does it matter?

A couple of years back, in Europe, as part of plans to meet the region’s climate commitments, a law called the Energy Efficiency Directive became law, compelling all datacentre operators above a given threshold to disclose policy-relevant information, like the annual energy consumption of a datacentre, water usage, how clean the energy was, and so on. We’re written at length about this (see all our posts so far)

The idea was this that information would be disclosed publicly, but as a compromise from operators who pushed back, there was a second law, called (deep breath) Delegated Regulation (EU) 2024/1364), that basically said:

If you don’t want to disclose publicly, you at least need to disclose privately to the country you’re in.

Given the absolute mania around datacentre buildout, and current plans in Europe to triple datacentre capacity in 5-7 years, knowing how much capacity there is right now, and how much energy is being used seems pretty important – especially if like us, you care about a fossil-free internet.

What did we see in the Netherlands?

We mentioned earlier that the EED was a law across Europe. In Europe because you have a federation of 27 different member states, like France, Spain, Greece and so on, each with their own governments and laws, the reality is that it’s a bit more helpful to think about the EED like a lower bar that each country is has to clear with its own laws by a certain date.

To make this concrete, in the Netherlands, even if datacentre operators did not disclose publicly the information required in the EED because of trade secrets of commercial confidentiality, they still had to at least disclose the information to the Dutch government, so the government can understand what’s happening in the sector, and then share the data central to the European Commission, to provide a view across Europe, and to provide some kind of evidence base for future decisions.

However, because this directive is a lower bar, it also means that different countries can have slightly more ambitious interpretations of the law, and in some cases can go beyond what was written in the original directive. For example, in France with another disclosure law called the CSRD (the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive), if you are a director of a huge company, and you are seen to interfere with the reporting, you can go to prison, even if the original directive didn’t go that far. Similarly, as we’ve covered elsewhere, in Spain, there’s extra language about disclosing how many jobs have really been created over time vs what was promised, and so on.

There was something special about the Netherlands though – these disclosures from datacentre operators were published on the Dutch government website in redacted form, respecting where the operators had chosen not to disclose specific bits of information. You can download themself to see what companies have decided is confidential and what isn’t, but crucially it also gives us an idea of who reported, and who didn’t.

Remember, the data that was redacted in public reports was still shared on to the European Commission to publish in aggregated form – if people are going to make policy decisions about how tens of billions of euros are spent in a region, you’d hope there was some kind of evidence base to justify it, right?

What are we learning so far?

The work by Leitmotiv goes into much more detail, comparing what was reported vs information already in the public domain about the Dutch datacentre sector, but in brief, here’s what they found:

- Many data center facilities did not report anything at all

- Disclosure is particularly low for US and UK-owned datacentre facilities in the Netherlands

- Lots of facilities are withholding information on environmental impact and energy consumption

- The existing stock of datacentre facilities is nowhere near full capacity

Why is this important?

To begin with, when we look at the first three findings, you might start with laws really should mean something – laws don’t really work if some players can just choose to ignore them.

For example we can look at one large company, Google. They have sizeable datacentre north of Amsterdam, that is already listed in the public domain on a site like OpenInfraMap, that they talk publicly about on their own website, but we don’t see evidence of any disclosure like the law requires. If you follow the links above, you’ll see another massive datacentre facility on the map shown as owned by Microsoft, near Google’s building. There is some limited disclosure we think we can point to, but once again, a lot of information is redacted.

Even when there is data missing, the gaps in the data can tell us something, especially when you compare it to what is expected for the Netherlands. For a start, reported energy appears to be less than a quarter of what previous sector level estimates might be from the Dutch governments estimates. We’ve included the figures below.

An impact of poor disclosure – government targets before evidence

The final finding from Leitmotiv also calls into question the whole narrative of manic datacentre buildout.

If datacentre facilities are nowhere near capacity as the data Leitmotiv have collected suggests, and operators are reserving much more power on the grid than they are actually using, then it raises other questions.

If we already have a load of spare datacentre capacity in a region, why do we need to double or triple datacentre capacity in the next 5-7 years at all?

Would it not make sense to use what we have first, before building loads of new infrastructure we’re not sure we’ll need? Could we not allocate some of this future grid capacity and limited clean power generation to prioritise decarbonising other key sectors in a country, like transport or heating?

These are all questions that you need data to help answer, and hopefully with the next EED day being in May 2026, there might be more light shed in the Netherlands.

What’s the story in Germany?

However the Netherlands is not the only datacentre market in Europe. The Netherlands is the third largest market for datacentres in Europe right now, but Germany is the largest, and it has had its own law, the Energy Efficency Law (known as the EnEfG) for two years now – are we seeing a similar story?

The German datacentre disclosure laws have similar provisions to require disclosure of information publicly, with the same get-out clause as the Netherlands. But once again, datacentre operators still have to disclose to the German government, even if they do not disclose publicly.

And again, this information gets shared centrally to the European Commission, who earlier this year published some aggregated figures at a country level. So, even if we don’t have the level of transparency of the Netherlands, we can still draw some conclusions.

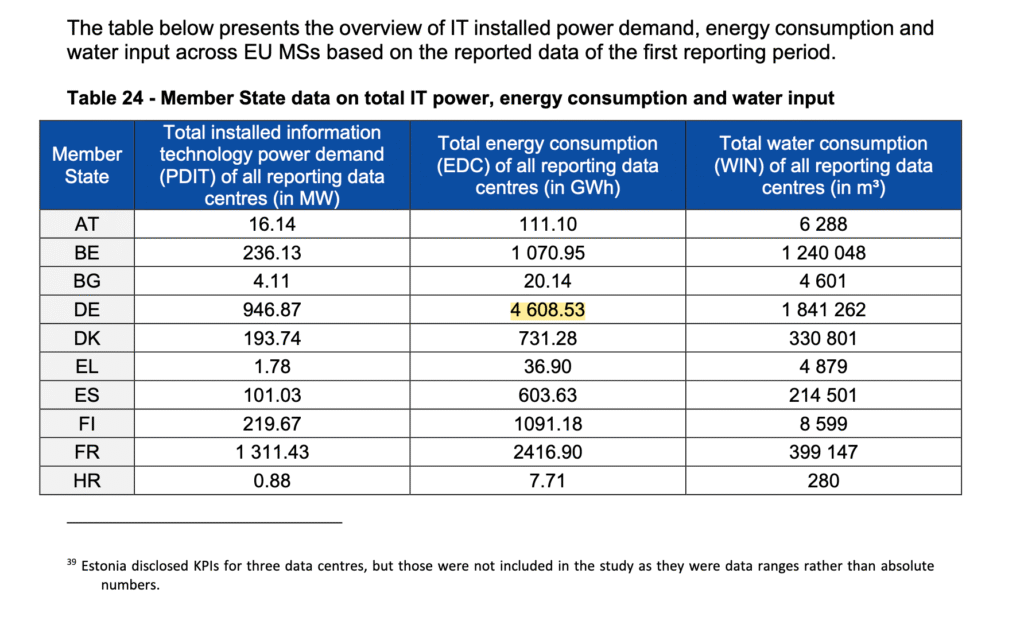

Let’s look at the numbers from the recent report from the European Commission, Assessment of the energy performance and sustainability of data centres in EU First technical report. Tucked away in the Appendix we can see some reported energy consumption figures from various countries. DE is Germany, and we have highlighted the reported figure for energy consumption from all disclosing datacentres in the country – 4608.53 Gigawatt hours (GWh).

What is this telling us?

4608.53 Gigawatt hours (GWh) is a huge amount of energy. It’s also a bit unwieldy, so for readability, and easier comparison later, it’s helpful to express it in a larger unit – Terawatt hours. There are a thousand Gigawatt hours in a Terawatt, so we can express this as 4.6 Terawatt hours (TWh) instead.

For Germany, 4.6 TWh for the datacentre sector is suspiciously low – it’s about a quarter of what you might expect.

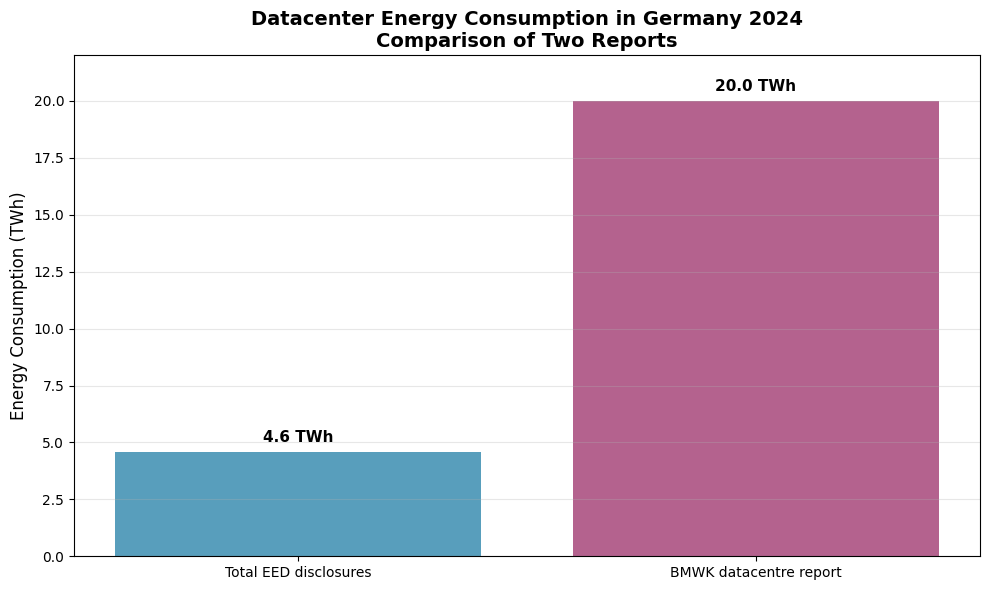

In January this year, the Germany Ministry of Climate and the Economy (the BMWK, now renamed the BMWE) published a report with it’s own estimates of the size of the German datacentre sector in 2024, based on expert analysis and tracking sales figures of various components in Germany. Helpfully, it also published an executive summary in English – Status and development of the German data centre landscape – Executive Summary, and there’s a convenient quote:

In 2024, data centres and smaller IT installations in Germany required 20 TWh of electricity, a figure which comprised around 4% of Germany’s gross electricity consumption of 517 TWh (2023).

Granted, the data we have from the EED is from the year before, in 2023, and the report we have above is from 2024, but they’re close enough in time to make some meaningful comparisons – let’s put them side by side:

Why such a big gap?

We know from an earlier post, that Germany eventually ended up with a fairly high share of datacentre operators actually disclosing information under the EED disclosure laws – about the 70% of companies who ‘should’ have reported did, and that combined energy consumption was around 4.6TWh – the small figure on the right.

This implies that the companies that didn’t report, the other 30% or so, are responsible for the rest – around three quarters of the missing energy consumption.

If the biggest consumers are not sharing information, you have to ask yourself – why?

One again, this raises all kinds of questions:

- How similar is the German situation to the Dutch one?

- Are the same actors not disclosing because they feel they don’t need to follow the same laws as everyone else?

- Who isn’t reporting, and what does the picture really look like if we do include their figures?

Wrapping up

We initially looked into these disclosure laws, because we care about a fossil free internet, and the laws covered how people power datacentres in Europe – we figured it would help us track progress towards a goal we share with lots of other people, and if you care about decarbonising the energy used to power the internet, you it helps to know how much energy is being used in the first place.

We still care about how energy is sourced, but in our own work, we keep coming across other questions that also matter.

Right now, it’s not easy to find answers to any these questions, not least because there isn’t really enough data in the public domain we can make sense of.

In Germany, our understanding is that we’ll see a data portal published early next year, which might shed more light in the largest datacentre market in Europe, and the next disclosure date is in May 2026.

We’ll update when we know more.