On this blog we’ve been written about the Energy Efficiency Directive, a European energy and transparency law a few times now. We’ve done this because we we care about a fossil free internet, and the law looks like it could give new insights into how far along Europe it to reaching this state, as well as driving companies to do more in terms of running greener digital services. We’ve been actively involved in the related workshops where the implementation of the laws and follow-on legislation is discussed, so in this post, Chris Adams, our Director of technology and policy, gives an update from the most recent workshop.

Before we get too far into this – what is this E.E.D. thing again?

We’ve written about this in more detail elsewhere (see our first post about it), but the short version is that it is a law in Europe that obliges anyone operating datacentres above a size threshold, for the first time ever, to report a whole set of information about energy use, water use, and how energy is sourced.

It has the potential to bring a long overdue amount of transparency to the tech sector, and creates an evidence base for effective, equitable policymaking in Europe that does not really exist at present. Also because reporting the data required is mandatory (thanks to an important, but unassuming sounding regulation, Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2024/1364), it sets a floor on the data quality that you can expect anyone operating a datacentre to maintain about its environmental impact.

This is useful because if you work in an organisation and you want to understand the environmental footprint of your own supply chain, you at least know what data exists now, even if it is not in the public domain.

At least, that’s the promise it offers.

An evidence base for policy making requires… evidence

In the European Union, this threshold for any datacentre is 500KW (kilowatts) of electricity power draw – this is comparable to about 1,000 households.

This might sound like a lot – and one of the worries when this law was being drafted was that a figure this high would miss out on a long tail of relatively small datacentres, that collectively represent a lot of energy being consumed.

This may still be the case, but in a world of AI and hyperscaler facilities there is plenty of energy consumption from larger datacentres to think about, and they are getting extremely large.

How large? Well, just in Europe, there are now headline grabbing datacentre campuses more than 2000 times as large as that 500KW threshold being built, like the planned 1.2 GW Start Campus in Portugal. For context, this is about 2,000,000 households – larger than most cities in Europe.

However, you can’t just rely on news headlines for policy – you also need meaningful reporting to build an evidence base.

So, is that happening?

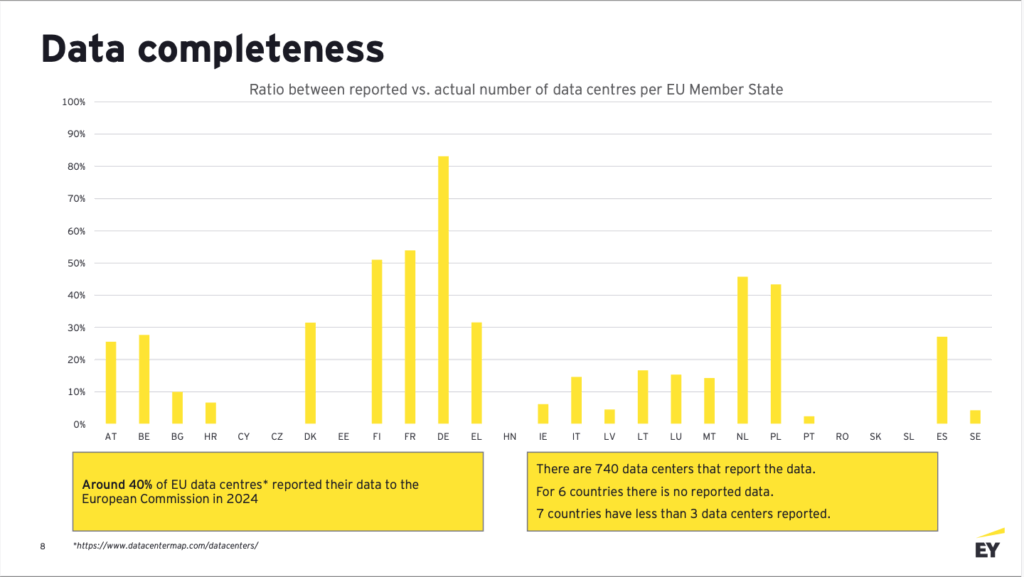

In the last post, we included a chart shared with us – of data reported by countries, versus the estimated number of datacentres you might expect to report in each country.

In the more recent workshop, we had a new chart shared with us – showing an update on who reported, now using a reporting percentage for each country now.

On the bright side, this shows some progress – in that we now have data from Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands, which was missing before. However, we lose a sense of the relative size of each country, and this can give the impression that there is more meaningful disclosure than there really is. It’s also harder to compare to the earlier state, to see if there has been any progress since we last looked at response rates from datacentre operators.

Showing how the reporting has changed

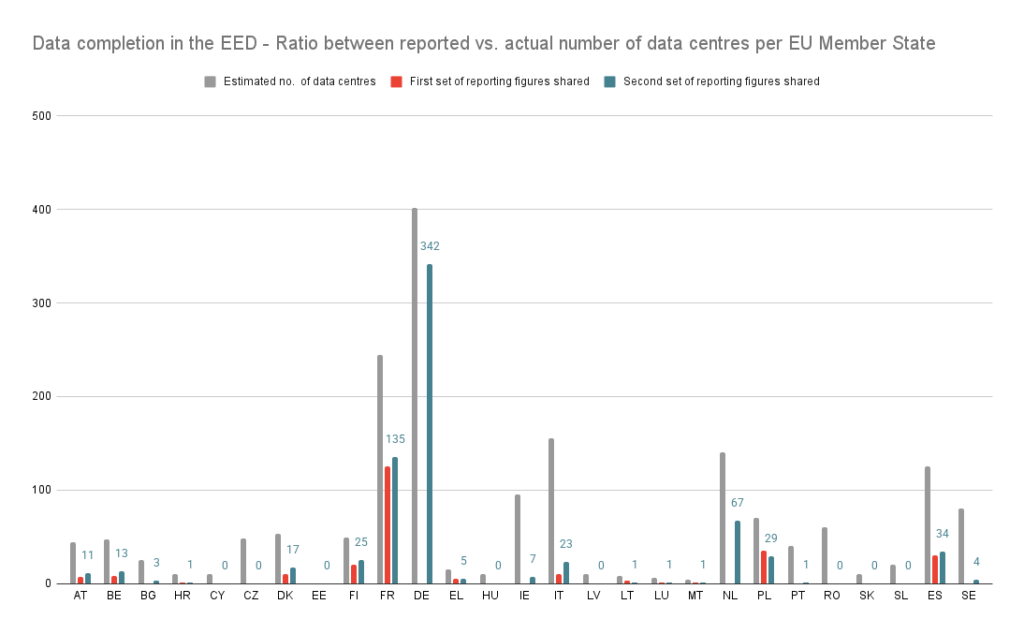

The chart above shows us three things.

- The grey bars show the estimated number of datacentres in each named country inside the European Union, shared by researchers with some of the best access to information in the industry.

- The red bars show a count of the datacentres that reported figures, for each country for the first E.E.D workshop.

- The blue bars with the numbers are our attempt to incorporate the updated “data completeness” shown in the chart above, so we have an idea in absolute terms for how many data centres are responding for each country. So for Ireland, rather than saying we’re basing this on info from 7% of total datacentres, we’d be saying we’re basing this info on 7 datacentres.

Now, we should be up front: we came up with these numbers by taking the percentage figures in the previous chart, and applying that to the estimated total number. This by nature is imprecise, as we’re working backwards from an image of chart rather than a data table. So, we’ve published the underlying spreadsheet we used for this chart, for others to improve upon, or submit corrections.

What does this tell us?

We see some progress in terms of there being data to base decisions and analysis on now, but in a few key areas, we still see a pretty disappointing response rate, particularly for smaller countries.

You really see this paucity of data in particular for Ireland, where at present around a fifth of all energy in the country is going to datacentres now, and where growth in relative terms has been the fastest (according to their own grid operator, around 85% of new demand on the grid between 2015-and 2023 has come from datacentres).

Ireland is also the place where new regulations have recently been published about connecting datacentres to the grid which very much incentivize on-site fossil fuel generation. This is problematic along a number of dimensions like air quality, climate change, supply chain resilience, cost, and so on.

Aside from that, why does this dataset matter?

Well, for one, we know that this dataset is likely to be used for making far reaching policy decisions, like setting minimum standards for datacentre efficiency and sustainability across Europe later in this decade.

For other laws in Europe, like the forthcoming Cloud and AI Development Act, which is likely to influence how billions of euros are spent in the sector, this is likely to be referenced too.

Minimum standards across Europe for clean energy and efficiency?

Speaking of minimum standards, one insight from the most recent workshop was a glimpse of what minimum standards might actually look like in Europe when they come into law.

We already have some minimum standards for datacentres in Europe. In Germany with their Energieeffizienzgesetz (Energy Efficiency Act) law passed a couple of years ago there is already now a mandate starting in 2027, that requires all datacentres above a given size threshold need to run on 100% annually matched renewable energy, and meet minimum efficiency standards.

It also requires a minimum amount of heat to be recycled for use by others (helpful when space heating is one of the largest drivers of emissions in the country).

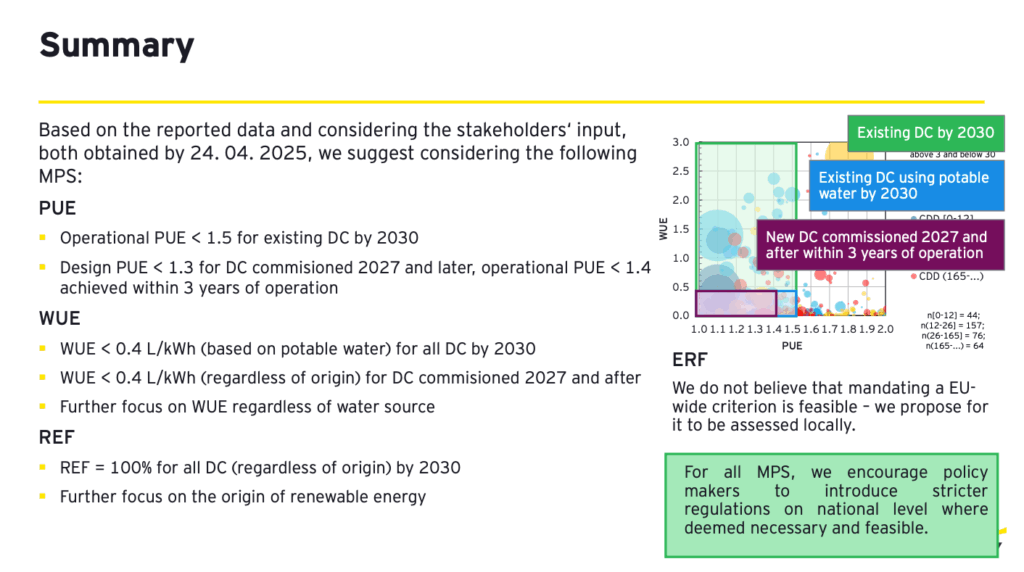

It now looks like we might see something similar rolled out across all of Europe. The slide below is a good (if somewhat dense) summary of the deck which goes into a lot of detail about the reasoning behind each set of minimum standards. We’ll present it, then explain what some of it means.

What is this slide telling us?

Let’s break this down in more detail, and decode some of the jargon and acronyms, to make sense of what is being recommended right now:

PUE – PUE stands for Power Usage Effectiveness, and you can think of it as a metric for how efficiently a datacentre is run, in terms of the energy is consuming going to actual computing versus trying to stop the servers get too hot. A high PUE is usually bad, and you ideally want it as close to 1 as possible, because the closer it is to 1, the closer you are to all the power being used for (hopefully useful) computation. The introduction of these minimum standards would likely mean that a long tail of older, often smaller, and much less efficient datacentres would need to either be shut down or refurbished. It would have a less of an impact on larger, newer datacentres, which tend to already to have a PUE value below 1.5.

WUE – WUE stands for Water Usage Effectiveness, and if PUE is concerned with how much extra energy has to go towards powering chillers and fans to keep servers cool. It’s typically expressed as a figure of liters of water withdrawn for each kilowatt hour of energy used, so a high figure means lots of later being used for each unit of electricity (and by extension computation). It’s important to understand that Water Usage Effectiveness refers to local water usage by the datacentre itself, not in the supply chain, so even though a larger share of water is often determined by the source of power (fossils fuels tend to use use more than renewables), this figure only is concerned with water being using locally that might compete with other localised uses like farming and so on.

This would be welcome for areas under water stress where datacentres sited in them.

REF – REF in this context refers to Renewable Energy Factor, the share of energy used by datacentres coming from renewable sources. A minimum standard of 100% by 2030, effectively means all power used by datacentres by 2030 would need to be green, across the entire European Union. For an organisation campaigning for a fossil free internet by 2030, this is pretty encouraging! Before we get too excited though – what matters here is the detail in the definition of what counts as renewable energy.

If the definition of renewable energy follows the definition currently used in German datacentre energy sourcing laws, it would still allow operators to run on fossil power (even using on-premise gas generators), as long as they buy enough “unbundled” clean energy credits from elsewhere within Europe the same year – this isn’t fossil free at all!

We think there are more rigorous standards to adopt, like the “three pillars” approach already written into law for European “green hydrogen” projects, which requires that energy is additional, timely, and deliverable. When talking about how ‘green’ energy the language can get quite technical here, so it’s worth unpacking briefly to help make sense of these details:

- additional in this context refer to new clean energy generation, that displaces fossil generation. So rather than claiming credit for a dam built 40 years ago, you’d need generation from new sources that are not powered by fossil fuels.

- timely refers to clean energy generated at the same time as it’s used – so no using solar certificates to count energy used at night as green. You’d need matching power, so either wind, batteries, geo thermal and so on.

- finally, deliverable refers to clean generation that has physical connection to where energy is used – so no using clean energy certificates in somewhere like Iceland to mark energy use in Poland as green. You’d need clean generation in Poland, or somewhere nearby with a physical connection instead.

We see this approach proposed in the Clean Cloud Act introduced in the USA earlier this year – if it’s being proposed there, and already law in Europe in another sector, it ought to be possible for the tech sector in Europe too.

Anything else?

The published workshop deck is worth a perusing, and available on the Borderstep Institute EDCDEAR webpage, along with previous slide decks.

If you are curious, you can also express interest in the next workshop yourself – follow the link to register for the fourth workshop on June 18th.

Update: at a separate event, some further information about minimum performance standards for datacentres in Europe was published. Here’s the deck – An EU energy label for data centres.